Discovering more about river crossings at Shincliffe.

SLHS wishes to thank the Architectural & Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland for their support of this project.

Introduction

There has long been speculation in the local community about a possible Roman crossing of the River Wear at Shincliffe, fuelled by the discovery of timbers in 1983. In talk to Shincliffe Local History Society (SLHS) in 2011 about his work, Gary Bankhead mentioned that he had seen timbers and dressed stone in the Wear at Shincliffe, having been unaware of the mediaeval bridge. Subsequent discussions and research eventually led to the project for which the Architectural & Archaeology Soc. of Durham & Northumberland (AASDN) kindly provided a grant in 2024.

Setting

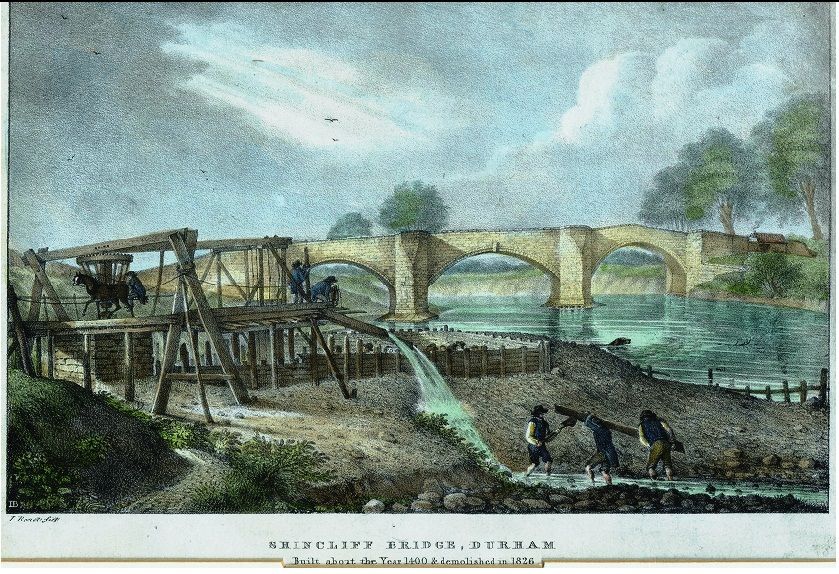

One and a half miles South West of Durham, Shincliffe mediaeval bridge was approx. 100 yards upstream of the present bridge on the road. A177 (Stockton – Durham) shown below on the 1st ed. OS 6 inch (1857). (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1: Showing setting and location of the modern and mediaeval bridges at Shincliffe

Historical Background

The existence of “Cades’s Road” from its crossing of the River Tees at Middleton One Row, through Sedgefield park, along the alignment of the A177, had fuelled speculation that there could have been a Roman crossing of the River Wear at Shincliffe.

There is documentary evidence relating to bridges at Shincliffe from the 13th century. However the evidence of the number of structures built de novo is very slim.

The first reference to a bridge is in the will of John Burgh, chaplain of Durham, dated 11th March 1290 ( Durham Cathedral Archive ; GB-0033-DCD-Cart.4 f.219r-v) in which he left £4 12s. 1d. for arrears of the masons working on Shincliffe Bridge, and 18s for lime and stones bought.

The Durham Account Rolls in 1368 included 11s-4d towards making a bridge according to E Jervoise in his book “The Ancient Bridges of the North of England” (SPAB in 1931) however whether this meant that the earlier bridge needed replacement or had fallen is not known. Also in 1370 Bishop Hatfield issued a Commission of Inquiry concerning land for the repair of the bridge but it is not clear how this relates to the expenditure in 1368.

In 1385 Bishop Fordham appointed a further Commission of Inquiry as the bridge was said to be ruinous. This would appear to have led to action as there is afragment of an agreement for the repair or rebuilding of Shincliffe Bridge dated 12th April circa 1387 in the Durham Cathedral archives. (DCD Misc.Ch. 7215.) and may possibly have resulted in what is known as the Bishop Skirlaw bridge (the immediate predecessor to Bonomi’s bridge) which was built in approximately 1440, so named in the 1753 engraving. Whether this bridge was a new bridge or rebuild to some degree is not clear it and it may well have been in the same position as the previous structure.

According to Jervoise in 1537/38 the bridge is believed to have suffered severe damage by a flood because of lack of repair and a return of 1564 had noted the decay of Elvet and Shincliffe Bridges (Mickleton MS xxxvi, fol. 317). Margery Wren of Sherburn left £6-13s-4d in her will in 1540 for a new bridge. This bequest may have been used to pay for repairs as there is a Bill dated 14 August 1589 for repairs to Shincliffe Bridge in the Durham Cathedral archives. (DCD Misc.Ch. 3188). This was followed by an account for repairs to Shincliffe Bridge dated 11 February 1590 also in the Cathedral archives (DCD/L/LP22/206).

The bridge must have been in a reasonable condition for the visit of Charles I’s visit to Durham, en-route to Edinburgh for his coronation as King of Scotland in 1633. A new route for his entrance to the City was made from Shincliffe Bridge, North-west into Old Elvet. This ran across to, and around Nab End, under Maiden Castle and across Hollow Drift. (Victoria County History) so avoiding the steep difficult ascent of Shincliffe Peth normally used at that time. This route was eventually abandoned because of river erosion at Nab End.

Fig. 2: Shincliffe Bridge 1753 engraving showing extensive damage resulting from a 'violent flood' on 17th February 1753.

In 1753 Skirlaw’s bridge was again damaged by a flood, illustrated by a contemporary engraving of 1753, in the “Pictures in Print” collection from the Palace Green Library, (Fig. 2, above), showing the bridge with a pier standing in the river and two arches and a pier to the west (right hand side) in a collapsed state. The title refers to the construction date of about 1440 and that two arches were “forced down” by a violent flood on Saturday 17th February 1753, following a sudden thaw and heavy rain the day before. The bridge was repaired once again and there is an account in the Cathedral archives (DCD/B/AA/9) dated January 1771, for stone for Shincliffe Bridge. According to the biography of Bonomi written by the Durham historian June Crosby, (Ignatius Bonomi of Durham, Architect, by JH Crosby (City of Durham Trust 1987) which deals in some detail with his work at Shincliffe described below, by 1824 there was considerable public interest in the rebuilding the old Skirlaw Bridge as it was unsuited to the heavier traffic of the day on the main route from Stockton to the City. It was narrow and had a steep gradient up from the Shincliffe side, as well as the higher arch on the Durham side produced by the repairs after 1753.

A print of about 1824, illustrating the early stages of the construction of Bonomi’s bridge, (Fig. 3, below), shows the complete Skirlaw Bridge in the background.

Bonomi, the County Bridge Surveyor, investigated the condition of the Skirlaw Bridge and he found the Skirlaw Bridge was in a poor condition. The foundations were laid on frames of oak timbers on gravel and sand, visible under the collapsed pier in

(Fig. 2, above). “Fendering” by timbers packed with stones on the upstream side was the only reason it had survived. Reconstruction or widening was not feasible. Repeated borings were needed to find foundations suitable for a new bridge.

Fig. 3: Shincliffe Bridge 1824

Bonomi’s design was for two flat elliptical arches, with a causeway arch at the village end. The carriageway is 20 feet wide, with only a slight rise to the centre of the bridge. A second pavement was cantilevered out on the upstream side in the second half of the 20th century.

On 5th May 1824 the Deputy Clerk of the Peace advertised one or two contracts to be let for the taking down and the rebuilding of Shincliffe Bridge, together with the construction of a temporary wooden bridge to be used until the new bridge was passable.

The proposals were to be considered on 5th June 1824. Plans and specifications could be seen on application at the offices of Mr Bonomi, County Bridge Surveyor, Old Elvet. The contract for the new bridge was won by Mr Burnett of the City with a tender of £4,310.

Unfortunately records of Bonomi’s designs are very sparse and those in The National Archives are only private commissions in the papers of his various clients. There is no record or plan of the temporary bridge. All that is known from the Quarter Sessions Order Books (CRO QS/OB/20 & 21} is that on 14th May 1824 the job was awarded to William Howe, joiner of Sadler Street, Durham, at £143, which is about £13.5k now according to the Bank of England inflation calculator.

No report has been found about the form of the temporary bridge or whether the use was limited in any way as regards weight or width. Also, whether the use for heavy traffic of the old ford, which was roughly at about the location of the new bridge, was possible during construction is unknown. It is possible that a cheap solution, using a trestle type construction would have sufficed. This would probably have required some support in its span which could have been simple columns standing on stone sole plates.

Bonomi's formal certification of completion of the new bridge was reported to the Quarter Sessions in January 1827 so it seems safe to say that it must have become useable in 1826 which ties up with references to it being 2 years in construction.

The Quarter Sessions records also show that some stone from the old bridge was recovered and stored. In 1828, about a year after the current bridge was completed, the construction of an oven at Durham Gaol (the current Prison) for the incineration of verminous clothing brought in by prisoners was approved using stone from Shincliffe bridge.

The River Bed

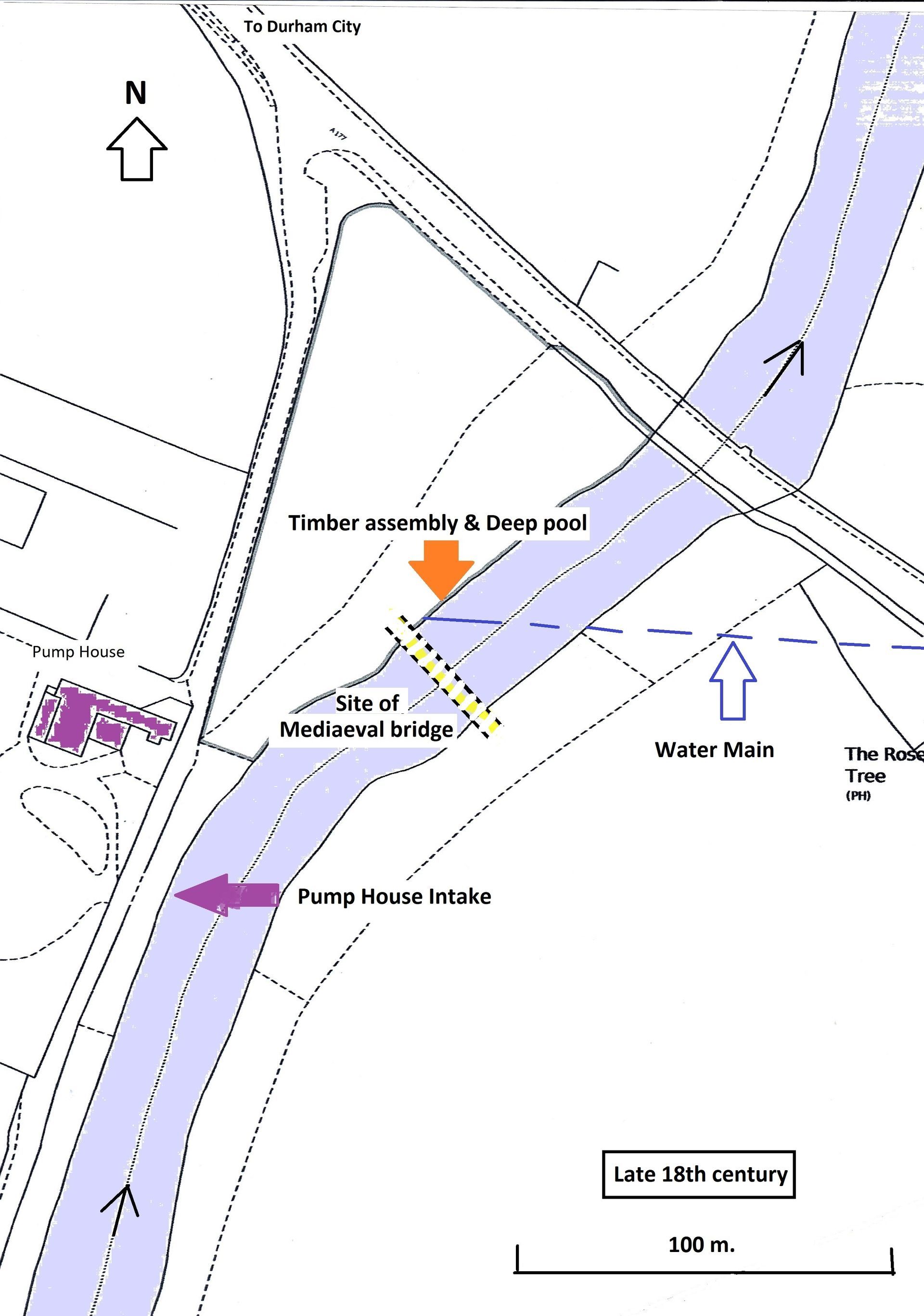

The first mains water supply for the City involved water pumped from the river by the Pump House up to a reservoir at Mount Joy in 1840. Water was abstracted into the filterbeds (Fig. 4, right), where there appears to be a calm, deeper area, upstream of the mediaeval bridge. The river bed then becomes shallow from the mediaeval bridge site down stream for some distance, littered with stone and brick.

Between the mediaeval bridge site and the location of the timber structure there is the remains of a water main which was built in the 1870’s diagonally across towards the Rose Tree pub to supply Shincliffe and the area eastwards. This water main involved a lot of brickwork to protect the riverbank and there are indications of a low brick wall just underwater which may have carried or protected the pipe across the river.

Immediately adjacent to the timber structure there is a deep pool, estimated to be approx. 4 m deep, down to bedrock. It is possible that this has been created by an eddy at times of flood flow caused by the remains of the watermain crossing the river on a diagonal alignment. This pool held a number of dressed stones which were recovered.

Fig. 4, right:

Investigations

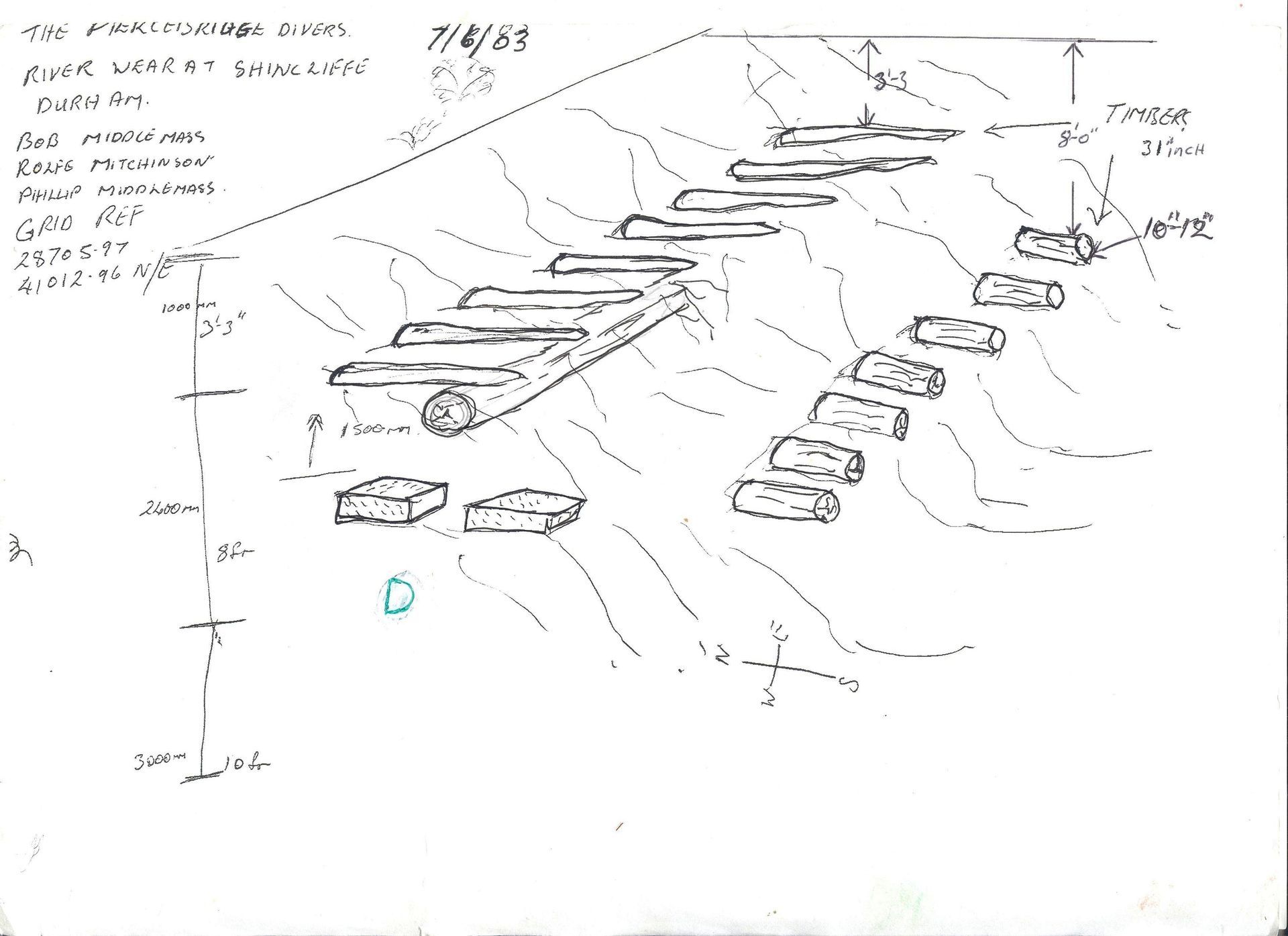

The mediaeval bridge position was scaled off from current bridge and pegged out on 6th June 2024. In 1983 the “Piercebridge divers” had recorded an assembly of timbers underwater approx. 4m wide in the western riverbank (Fig. 5.). This was found to be approx. 22m downstream of the position of the mediaeval bridge.

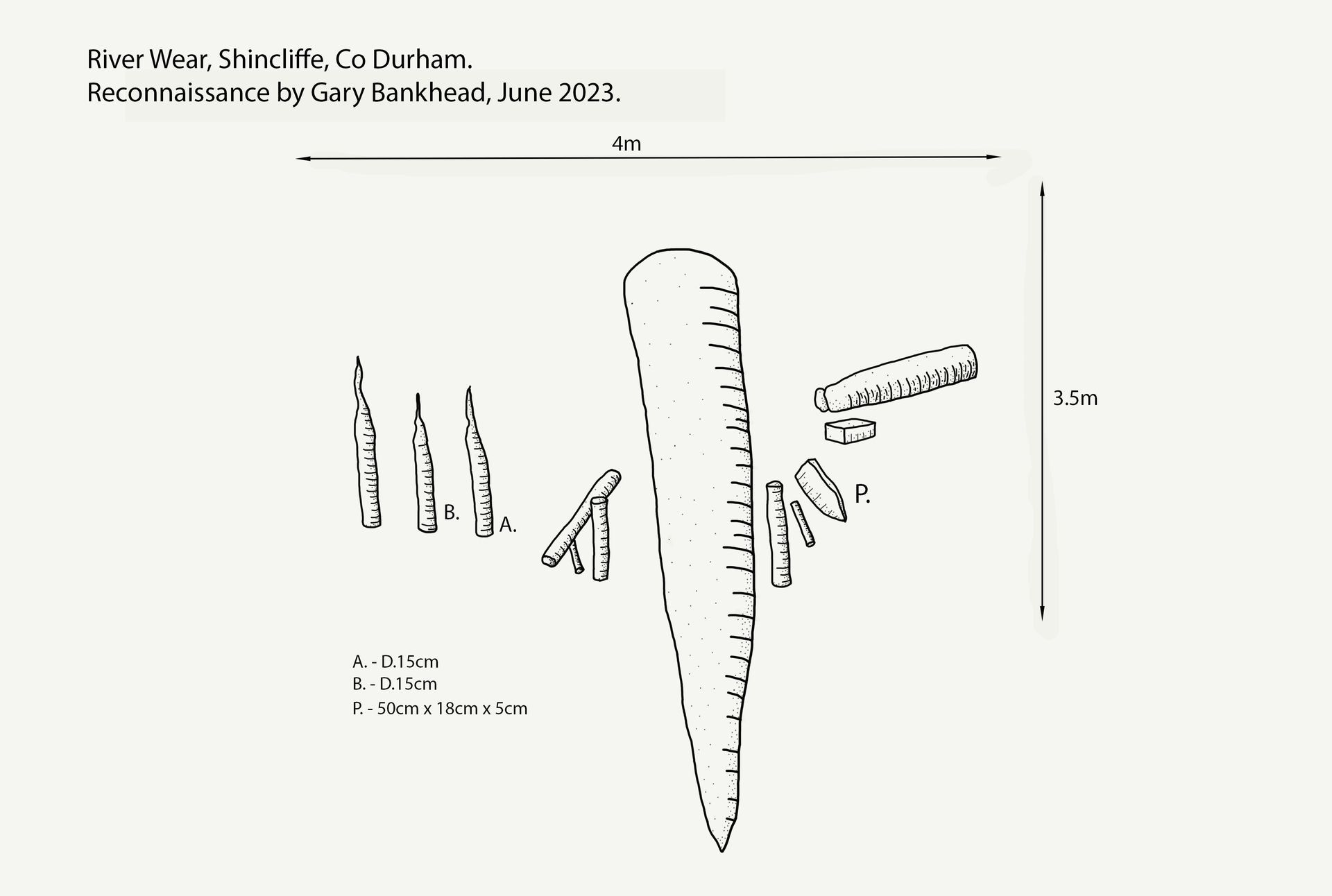

When Gary Bankhead carried out a recce dive in 2023 he estimated that 60% had been lost, due to erosion and the collapse of a tree from the bank above (Fig.6.). The position had deteriorated further after the winter 2023/24. The timbers had been lost and there were three vertical stakes with a horizontal plank end projecting out horizontally.

Fig. 5 Below left: Sketch of the timber assembly made by the Piercebridge Divers in June 1983.

Fig. 6 Below right: Sketch of the remaining assembly made by Gary Bankhead in June 2023.

Two vertical round, post-like timbers were recovered on 9th June 2024 in Dive 1:

Post 1 (Figs. 7), was 119cm long by 45 cm circumference and approx.10 cm dia., badly eroded except for the tip which has clear hand tooling marks.

Post 2 was 1.5m long, approx. 51 cm circumference and 14.5 cm dia., was considerably eroded for approx. 1/3rd of its length and the tip broken off. Sections were cut but proved to be unsuitable for dating due to being elm. The remaining pieces were returned to their original positions and the tip of post 1 was saved.

Figs. 7:

The second Dive on 27th June targeted a large rectangular section to timber protruding from the bank that had been seen on 9th June. This was found to have been washed out and vanished. However, a large brick-shaped block remained embedded beneath the lost timber, possibly a supporting chock, 26 cm long, 12 cm wide a 7 cm thick, (Fig. 8, left). This was recovered, a section cut and sent for dendrochronological dating. Dr Moir, of Tree Ring Services, Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire, received the sample on 5th July and confirmed that it was oak with circa 60 rings and the sample would be slow dried before the analysis.

He finally reported that there were only 43 rings and as dendrochronological analysis generally requires a minimum of 50-60 rings no further analysis was undertaken. Due to the failure to date this sample there were no costs.

Subsequently a sample of the outermost rings of one of the elm posts was sent for Carbon 14 dating to the Chrono Centre at Queens University, Belfast, and the result was +/- 22 years of a median date of 1838. i.e. 1816 to 1860 (C14 dates are from a base date of 1950).

Fig. 8: Rectangular block of wood (oak) recovered on Dive 2.